I recently had the opportunity to travel to Budapest for work, an opportunity I relished not only as a chance to learn something new, but also as a chance to spend some time in a new place. As it turned out, I learned far more than I had hoped at the training, though it got in the way of my exploring. There is a lot to see in Budapest, which is already two cities rather than one, and my glance across the surface left me with a longer list than I had when I arrived.

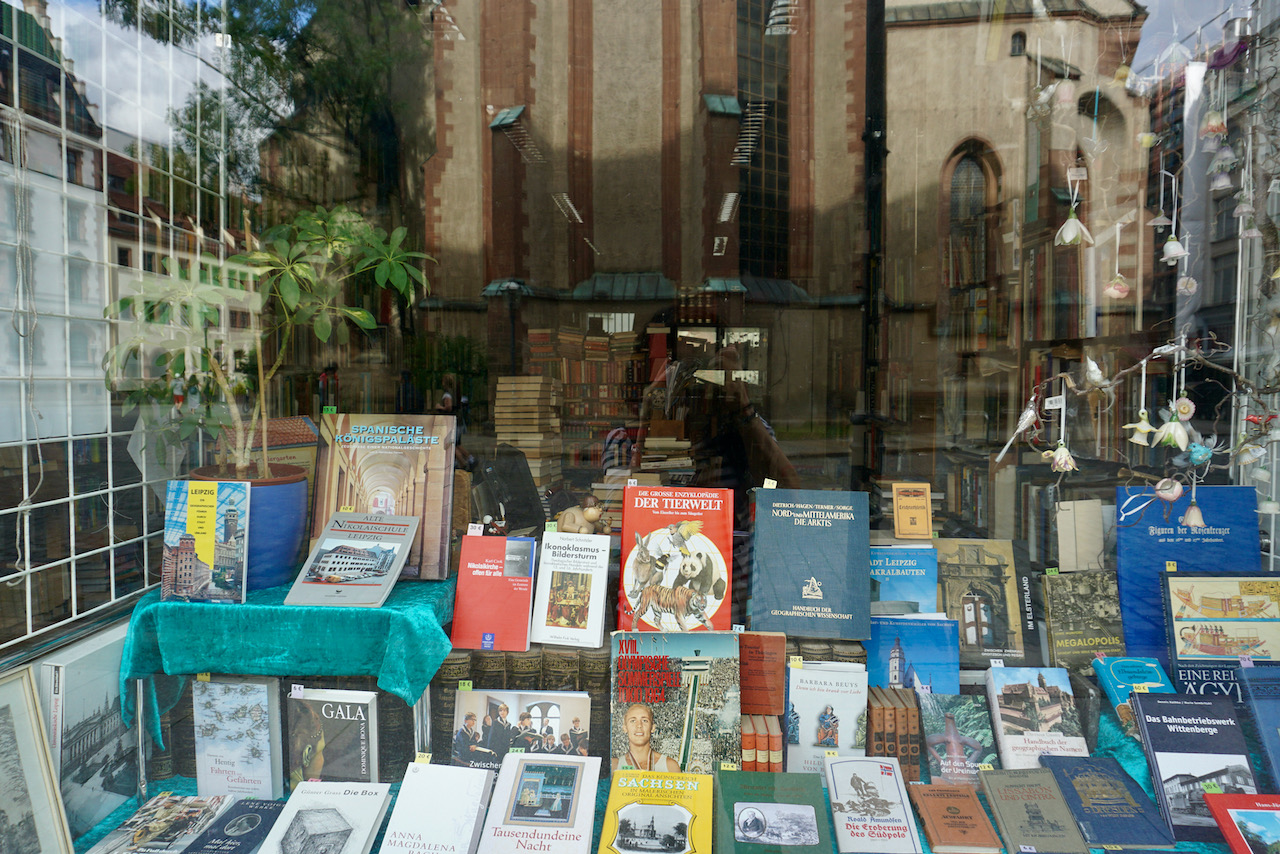

After deciding I liked Budapest upon first seeing one of its many street bookstalls, I stood in front of Europe’s largest synagogue, completed in 1859. It surprised me that Dohány Street Synagogue is located in a country that is 99% Christian, according to my tour guide, in a city with restaurants serving food from all over the world, and that’s something I love about visiting new places.

I was staying on the Pest side of the Danube and that’s where I took a walking tour the afternoon of my arrival, always my favourite way to see a city and learn its history. We saw the landmarks Budapest is known for, such as Europe’s largest Parliament . . .

. . . the Hungarian State Opera . . .

. . . St. Stephen’s Basilica . . .

. . . the Danube River and Széchenyi Chain Bridge (unfortunately closed to pedestrians due to construction) . . .

. . . and walked through a few of the parks that are an important part of local life.

It was on the walking tour that I learned about the monument that went up overnight in 2014, an attempt to change the narrative of Hungary’s role in World War II. The counter-monument placed by the people of Budapest aimed to rewrite that wrong.

It came as a surprise that history was being rewritten in a city with a memorial called Shoes on the Danube Bank, commemorating the 3,500 people told to remove their shoes before being executed and their bodies thrown into the river during the Arrow Cross terror of 1944-1945.

This memorial is on the Pest side of the Danube and, with eyes towards Buda on the other side, I headed over to do what I always try to do in a new place: Find the highest point and look down. In Budapest, this meant crossing the bridge to Buda and walking up to the Citadel.

Once in Buda, I walked along the Danube, marvelling at the force of the wind that cooled the air that had been steamy and humid when I arrived the day before. I went up to Buda Castle and looked down again.

I left by bus when it began to get dark. There was so much more to see.

With the time I had outside of the training, other wandering was an exploration of ornate doors . . .

. . . murals . . .

. . . and buildings that I liked for their appearance, a mix of architecture from before the wars, the Soviet period, and the time since.

I walked along Andrássy Avenue to its end at Heroes’ Square . . .

. . . and came upon Vajdahunyad Castle, build in 1896 to mark the millennium of Hungary’s beginning as a modern state; it’s an art museum today, one of many in Budapest.

Making mental lists of what I still wanted to discover, it was time to go. I left Budapest having tried new foods, made plans for a new role at school, and learned to greet, thank, and bid farewell in Hungarian. As always when travelling, I left with more than I had when I arrived, and I left grateful for the opportunity to be there.