Both my partner and I have long dreamed of going to Marrakech, and this seemed to be a good point in our lives to make that happen. After consulting with friends who had lived in Tangier, we had a sense that this would not be our only visit to Morocco, and this feeling only intensified after our three nights in Marrakech. We’ve both had the fortune and opportunity to see a bit of the world and neither of us have ever been anywhere quite like Marrakech.

Upon landing in the late afternoon, we took a bus from the airport to Jemaa El Fna, the main marketplace in the old city, or medina, of Marrakech. From there, we navigated twists, turns, bikes, mopeds, and donkeys before arriving at the alley that we would have missed had we not been looking for it. A few twists and turns later, we entered our riad, the guesthouse build around a courtyard that would be our oasis during our visit. Riads are quiet havens that have existed for centuries as family homes; the windows face the courtyard, so there is practically no noise that comes in from outside. Ours contained, as is traditional, a fountain of running water and a good deal of flora, including a date palm that was home to a family of birds. No alarm clock needed, assuming you’ve slept through the call to prayer that comes in the middle of the night and then earlier than the birds. (Spoiler alert: You haven’t slept through anything, but it’s all rather charming.)

Breakfast was served on the rooftop terrace and the suite that we booked (yes, we went all out for this one) included a living room and a sitting area in the airy corridor. We were served sweets and mint tea on arrival, and we knew we were in a different world.

As we would learn, rooftop eateries are common and we intentionally sought them out.

We could usually see cats, a common feature of Marrakech, jumping around the rooftops, and while they are very pretty, they do come along and beg. Understandably, the restaurant cats are definitely better off than the cats eking out a living under park benches.

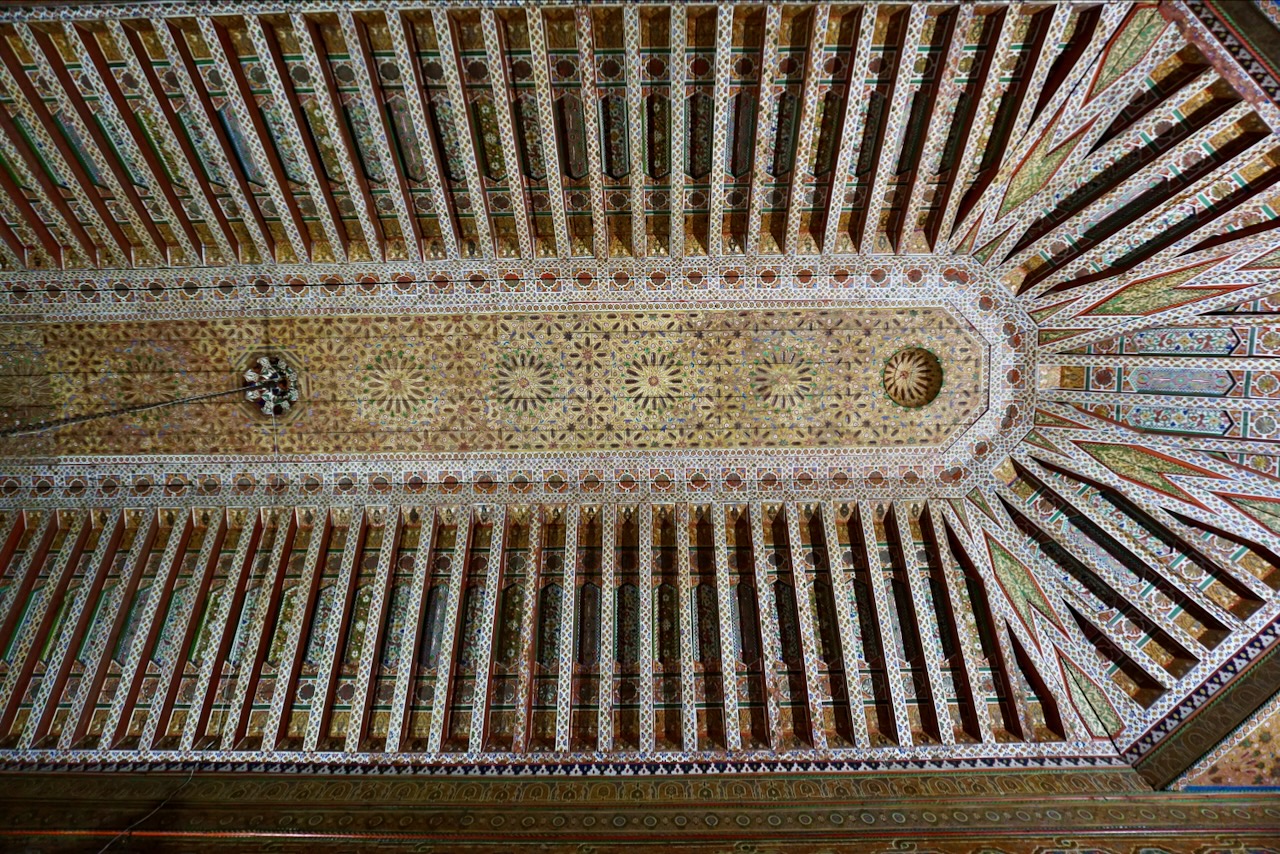

From that first walk through Jemaa El Fna, however, we were enchanted. The market, and particularly the main square, contained everything we’d always imagined about Marrakech, and we spent our time there grinning at being caught on a film set, surreal snake charmer music (and snake charmers!) included. In addition to the snake charmers, monkeys on leashes, and horse-drawn carriages, there were vendors selling all manner of items to buy, in all colours, in all scents. We never tired of looking, and the indoor market sections were surprising cool due to the slatted wooden ceilings that kept out the sun.

Taking the advice of our riad host, we did our best to bargain prices down at least 60% of the original asking price. We weren’t entirely successful, and we definitely bought a few things priced for tourists, regardless of haggling, but we never paid full price and we did walk away a couple of times. Overall, we found the vendors and shopkeepers respectful and less pushy than we’d been told to expect. They were also extremely flexible, switching immediately into a different language if we didn’t respond in whichever one they tried first. Just for fun, I used as much French as I could, but it’s amazing to see how little French I can still speak.

We were also pleasantly surprised by the amount of green in the desert of Marrakech. Our tour guide on our first morning told us that the water comes from the north, from the Atlas Mountains where mint grows, and that the centuries-old irrigation systems were hidden underground as protection against invasions. We saw pomegranates, olives, dates, and oranges growing from trees, and the tour guide explained that fruit from trees in the parks are free for the taking.

Standing in the shadow of Koutoubia Mosque, we learned about the history of Marrakech . . .

. . . and later walked through a couple of the ancient gates to the city.

We so taken with the winding, narrow alleyways, designed for protection from invaders and sunlight. Additionally, the windows and doors were in shapes that we are not used to seeing, adding to the sense of being in a different world.

One of the best opportunities to see the architecture, tiles, carved and painted ceilings, and ornate calligraphy that characterize Marrakech is to visit the Ibn Yusuf Madrasa, which dates to the sixteenth century. This former Qur’an school has been preserved as a museum, and it is stunning.

The same can be said for the Bahia Palace, built in the nineteenth century, which also contains beautiful gardens in the riad courtyards. Much of the palace, like much of the city, was undergoing renovations from the earthquake in 2023, however, so there was a lot we were unable to see.

The former Jewish Quarter is located nearby, and it was heartwarming to have heard from the tour guide about the very positive and protective relationship between Muslims and Jews in Morocco. He explained that while Jews were not persecuted there, considering Judaism is an Abrahamic religion and the Abrahamic religions are traditionally recognized and protected under Islam, there were fears of invaders, and the Jewish Quarter was deliberately surrounded by other sections of the medina as a means of security.

It took us several alleyways to make our way to the Slat al-Azama (or Lazama) Synagogue, founded in 1492 following the expulsion of Jews from Spain. A small museum located on the other side of the riad courtyard contained images of Jewish communities, life, and culture across Morocco and other parts of Africa.

A visit to Marrakech, we were told, is not complete without a view of Jemaa El-Fna at night. We climbed the stairs to a rooftop café that exists for the purpose of said view, purchased the required beverage per person, and took in from above the hustle and bustle that we had experienced from below.

Marrakech is an overwhelming sensory experience and we retreated to the quiet of our riad each afternoon to gather and recentre ourselves. By the time our third and final morning came around, we had seen what we wanted to see and were ready for a change of pace. We basked in the calm of our riad before heading to the airport and I fell asleep immediately on the plane, exhausted from everything we’d taken in. The snake charmer music, which I was delighted to find out is real, had acted like a portal into a different world and, grateful for our time there, we could leave it behind. I never need to go back to Marrakech, but I’m so glad to have been there.